The Nordic brown bee

- Home

- Our work

- Farm animals

- Nordic native breeds

- The Nordic brown bee

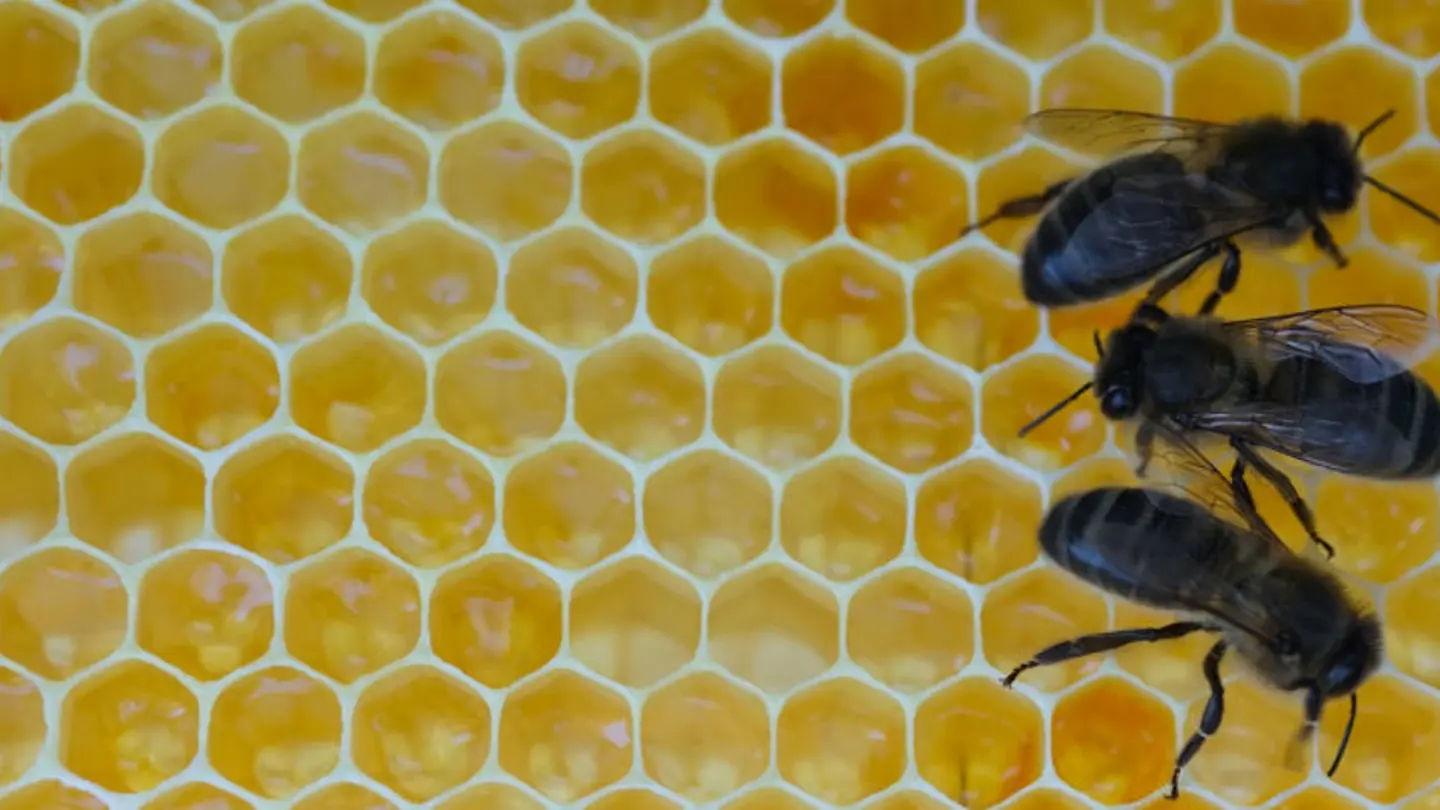

Honey bees are threatened by intensive agriculture, habitat loss and climate changes worldwide and are important to conserve, not only due to their honey production but also due to their pollination services. Three-quarters of the world’s crops and one-third of the world’s crop production is based on insect-pollinated plant species, and honeybees represent an important pollinator. Honey bees also provide other products, such as pollen, beeswax and propolis.

Today, there are four main types of honey bees kept in the Nordic countries: Carniolan, Italian, Brown and Buckfast bees. The first three are sub-species of the European honey bee (Apis mellifera) and the latter is a human-bred hybrid bee. The brown bees are also known under the names: European dark bee and black bee. We consider the brown bee to be the original honey bee species in the Nordic countries. They originally developed in the Southwest of the Alps a few million years ago and migrated North after the end of the ice age and reached Denmark and southern Sweden about 10,000 years ago. Only in the last 100-150 years have the other sub-species been imported to the Nordic countries.

The brown bee (Apis mellifera mellifera) evolved under different climatic conditions in Europe and big seasonal variations, especially in the North. This has led to big variations in their characteristics and brood rhythm. In general, the brown bee is known to be hardy and frugal. They have a larger body size and longer hair than other sub-species. Their tongue is relatively short, which means that they leave nectar of flowers with deep nectarines to their colleagues: bumblebees and solitary bees, among others. The brown bees adapt their behaviour to the climate they are in. In general, it is often said that they are confident bees that are not in a hurry to fly early in the spring. In intensive agricultural areas, where arable plants typically have short-term, but intensive flowering, the brown bees cannot make the most of the early spring blooming. However, they may have an advantage in areas with flowering heather, and with dispersed nectar sources. In the Nordic countries, where the spring can be cold, and an early warm period could be followed by frost, it could be an advantage if the bees do not fly out too early. They are also known to fly even if the weather is cold and wet. The brown bees can therefore be a particularly good choice for the beekeepers in the Nordic countries.

Among the bee sub-species kept in the Nordic countries, the brown bee is considered worthy of preservation efforts because it is the native honey bee, and it is endangered with very few left of this bee worldwide. Other sub-species have been introduced everywhere, and due to the bees’ special mating biology, it has not been possible to prevent crosses. Queens mate with drones that can come from any hive within a radius of about 3-4 km, and in some cases even up to 20km. If the brown bees are to be maintained as a pure sub-species, conservation measures are necessary.

Beekeeping in the Nordic countries

We know little about beekeeping in the Nordic countries before the advent of Christianity. However, we do know that the harvesting of honey from wild bee colonies (honey gathering) has been practiced in both Denmark and Sweden since the early times. Even before the Middle Ages, Sweden had detailed laws on who had the right to the wild bee colonies in the forest, and on what conditions one could harvest honey from these. In Norway there is no certain historical documentation of beekeeping until the 18th century. However, the Vikings mention bees and honey (for mead) in their Sagas, and products from bees, such as honey and beeswax was used in Norway throughout the Middle Ages.

People were surprised when bees were found in connection with archaeological excavations in the Old Town in central Oslo in 1975. This material was dated to 1175-1225, and measurements showed that it was pure brown bees. Whether this is proof that beekeeping was practiced in Norway at this time as well, however, is an open question. Modern beekeeping, where the bees have been kept in man-made beehives, has been practiced since the 16th century both in Sweden and in Denmark. At the same time, publications from Swedish priests tell of widespread honey gathering from 1650 onwards.

Denmark

The Danish Beekeepers’ Association was founded in 1866. The goal was “to get the regular man involved and teach him to look after the bees in the best way, in modern hives with movable frames”. And one must be able to say that the Danes succeed: since the 1990-ies, 140 to 150,000 colonies have been kept in Denmark. However, there are very few brown bee colonies.

In 1990 there were around 400 brown bee colonies and today there is about 200 brown bee colonies in Denmark, most on the island of Læsø, in addition to some on the island Endelave, and a few apiaries scattered throughout the country. The number of beekeepers involved in the conservation work is about 20. The island of Læsø was one of the last places with pure brown bee colonies in the Nordic counties and today, a part of the Island of Læsø is conserved as an area reserved for pure brown bees as the only place in Denmark.

Sweden

As early as 1750, a survey was conducted of the prevalence of beekeeping in Sweden, and the results showed that there were 30,000 beehives in the country. In 2000, it was estimated that there were 110,000 beehives in in total Sweden and about 14,000 beekeepers. There are much fewer brown bees, with an estimated 2000-3000 colonies of brown bees in Sweden today.

Brown bee enthusiasts in Sweden have been working to build up the strain of pure brown bees (project «NordBi») since late 1980’s, with support from The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and later also the Swedish authorities. Breeding material has been based on the remains of Swedish brown bees, as well as imported Læsø material. Isolated places have been found that can be used for mating the queens (mating stations) and today there are several pure mating areas in several parts of Sweden — in northern Värmland, the whole of Härjedalen, most of Jämtland, parts of Medelpad, Västerbotten and Norrbotten. On the island of Lurö in Lake Vänern, there has been a mating station since 1984 where 800-1000 queens are mated every year. Half of these are exported to other countries in Europe.

Finland

The first bees were brought here from Estonia in the 1750’s. However, they did not survive the cold winters in Finland. The first surviving bee society was brought from Sweden in 1777 and placed in the garden of the Turku Academy in Ruissalo. The Finns were otherwise early in importing new species, as the first Italian bees came to the country as early as 1866. By the 1960s, pure brown bee colonies had almost disappeared. Only the Väinö Mäki strain has remained, which has now merged with other brown bee strains, and the current brown bee population in Finland come from Sweden and Ireland.

Today there is about 80,000 beehives in total, and out of these about 300 are brown bee colonies kept by approximately 30 beekeepers. Two breeders mate their queens on islands, each producing about 100 queens per year. One breeder produces about 30 queens per year in the deep forest, and more breeders are trying to start up breeding on islands. There is an association for brown bee beekeepers in Finland, which is also a member of the Finnish beekeeper Association. They are trying to recruit more beekeepers of brown bees. Thus, the keeping of brown bees in Finland is still under development.

Norway

The first reliable information about beekeeping in Norway is from 1740, when beehives were imported to Kristiania (now Oslo). The Norwegian Beekeepers’ Association was founded in 1884, which contributed to further increased interest in beekeeping, and the agricultural census in 1891 showed that there were about 17,000 beehives in Norway. In 1992 there were approximately 90,000 beehives. Norway has pure brown bees in parts of the Agder counties and Rogaland. In this area, one has mostly had this species since the beginning of beekeeping. In 1987, the Norwegian authorities approved the municipalities of Flekkefjord, Sokndal and Lund as purebred breeding areas for brown bees. This means that within these municipalities it is forbidden to keep bees other than pure brown bees.

The Norwegian Beekeepers Association has been breeding Brown Bees since 1976, However, they also breed other bee species. In 2013, the Norwegian Brown Bee Association was established to work on conservation and breeding of the brown bee. Today there are about 50,000 honey bee colonies in Norway, and around 4000 beekeepers. Of these, about 4000 are brown bee colonies from about 400 beekeepers, where 1000-1100 of the brown bee colonies are in legal conservation areas.

Iceland

The first attempt at beekeeping in Iceland was in Akureyri in 1935 and it lasted for several years, but unfavourable weather conditions and difficulties in importing led to its abandonment. The next attempt was in 1943 in Reykjavík and lasted until World War II. Both attempts included brown bees imported from Norway. The third attempt began in 2000 and is still going on. It is not clear how many hives are alive today, but in comparison with recent years, it can be estimated that about 120 hives are alive in Iceland today, all Buckfast bees.

Due to the large winter losses, there has been increased discussion about changing species to the Nordic brown bee. When importing bees to Iceland, one must be extremely careful not to import diseases or mites as Iceland is currently free of brood mites. Private initiative has been made to import carefully vetted brown bee queens to Iceland, and NordGen’s Nordic Brown Bee Network has aided in connecting this private initiative to other Nordic beekeepers. 10-20 queens each from Norway and Sweden will be imported privately. In addition, The Icelandic beekeeper association has planned an import of 4 fertile brown queens. The hope is that within a few years there will be viable brown bee colonies also in Iceland.

Brown bees outside the Nordic countries

There are brown bees outside of the Nordic countries as well. In an isolated area in the Maritime Alps in the south of France, queens are bred for sale in addition to an active network of beekeepers that have conservation areas in many parts of France. The starting point for these bees is the native French brown bees. This can be important material to take care of, as this area is considered the area of origin for the brown bees. In Austria, there are brown bees in Tyrol. From “Tiroler Imkerschule” you can buy purebred brown queens. In Switzerland, the breeding of Brown bees is well organised with several mating stations.

There is a large population of brown bees in Ireland and the British Isles, for example, the Island of Colonsay in Scotland. Isle of Man has banned import of other bees to protect from varroa mites, resulting in pure brown bees on the island. In the North-west of Italy, in Belgium and the Netherlands, small but pure populations occur too. Poland is having an active brown bee program; however, the local beekeepers are shifting more toward introduced bees. Germany has all but exterminated the Brown bees, with massive support for the introduced Carniolan bees.

Conclusion

There are two options when it comes to conserving genetic resources in bees: isolated living populations or the use of artificial insemination to exchange genetic material across borders. The former method is a very resource-intensive conservation method and artificial insemination is not widely available yet. Freezing of semen and embryos in a gene bank is also an option to conserve genetic material, but the technology for this need to be developed in addition to the best option being live, viable populations.

The brown bee is on the verge of extinction worldwide after dominating large parts of Europe until the 20th century. It is therefore of significant importance that conservation measures are implemented in those places where there are still pure strains of this sub-species. On an International level, SICAMM — The International Association for the Protection of the European Dark Bee has been impactful. In the Nordic region, significant work has been done through the Nordic Brown Bee Network, where experts from the Nordic Countries have come together to make an Action Plan, with an updated version in 2019. The action plan highlights and prioritizes actions for the conservation of brown bees. Cooperation amongst actors and coordination at national and international levels are of the utmost importance. More specifically, consistent characterization of bee populations in the Nordic region to facilitate the exchange of breeding material where necessary, and development and promotion of brown bee specific management techniques were identified as important conservation measures.

Most of the conservation work is done locally within each country. Without local beekeepers and their interest in conservation, the conservation work is impossible. Therefore, it is important to recruit new beekeepers and breed the brown bee with attractive qualities for beekeepers. The goal for the brown bee conservation work is to have viable populations of brown bees, with characteristics that beekeepers value, in each of the Nordic countries.

References

The Swedish Brown Bee Association: https://www.nordbi.se/

The Norwegian Brown Bee Association: https://norskbrunbielag.no/

The Association for Brown Bees in Denmark: https://brunebier.dk/

Læsø Brown Bee Association: http://brunbi.dk/

The Finnish Brown Bee Association: https://tummamehilainen.fi/en/yhdistys/

The Icelandic Brown Bee Initiative: https://www.beesiniceland.com/

Brown Bee Wiki: https://wiki.nordgen.org/brownbee/index.php/Main_Page

Nordic Brown Bee Network: https://www.nordgen.org/projekts/det-nordiska-bruna-biet/

SICAMM – The International Association for the Protection of the European Dark Bee: http://sicamm.org/

References

Aarhus, Asne. 1991. Bier og Mjød – i sagaen blott? Jord og Gjerning 1991. p. 79-87. Landbruksforlaget, Oslo.

Bertrand B, Alburaki M, Legout H, Moulin S, Mougel F, Garnery L. Mt DNA COI‐COII marker and drone congregation area: An efficient method to establish and monitor honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) conservation centres. Molecular Ecology Resources. 2015 May;15(3):673-83.

Bieńkowska M, Łoś A, Węgrzynowicz P. Honey bee queen replacement: An analysis of changes in the preferences of Polish beekeepers through decades. Insects. 2020 Aug;11(8):544.

Hassett J, Browne KA, McCormack GP, Moore E, Society NI, Soland G, Geary M. A significant pure population of the dark European honey bee (Apis mellifera mellifera) remains in Ireland. Journal of Apicultural Research. 2018 May 27;57(3):337-50.

Keith A. Browne, Jack Hassett, Michael Geary, Elizabeth Moore, Dora Henriques, Gabriele Soland-Reckeweg, Roberto Ferrari, Eoin Mac Loughlin, Elizabeth O’Brien, Saoirse O’Driscoll, Philip Young, M. Alice Pinto & Grace P McCormack (2021) Investigation of free-living honey bee colonies in Ireland, Journal of Apicultural Research, 60:2, 229-240, DOI: 10.1080/00218839.2020.1837530

L. F. Groeneveld, L. A. Kirkerud, B. Dahle, M. Sunding, M. Flobakk, M. Kjos, D. Henriques, M. A. Pinto, P. Berg. (2020) Conservation of the dark bee (Apis mellifera mellifera): Estimating C-lineage introgression in Nordic breeding stocks. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section A — Animal Science 69:3, pages 157-168.

Momeni J, Parejo M, Nielsen RO, Langa J, Montes I, Papoutsis L, Farajzadeh L, Bendixen C, Căuia E, Charrière JD, Coffey MF. Authoritative subspecies diagnosis tool for European honey bees based on ancestry informative SNPs. BMC genomics. 2021 Dec;22(1):1-2.

NordGen Nordic Brown Bee Network. 2019. The Second Plan of Action for The Conservation of the Nordic Brown Bee. Nordic Genetic Resource Center. Alnarp.

Parejo M, Wragg D, Henriques D, Charrière JD, Estonba A. Digging into the genomic past of Swiss honey bees by whole-genome sequencing museum specimens. Genome biology and evolution. 2020 Dec;12(12):2535-51.

Pinto MA, Henriques D, Chávez-Galarza J, Kryger P, Garnery L, van der Zee R, Dahle B, Soland-Reckeweg G, De la Rúa P, Dall’Olio R, Carreck NL. Genetic integrity of the Dark European honey bee (Apis mellifera mellifera) from protected populations: a genome-wide assessment using SNPs and mtDNA sequence data. Journal of Apicultural Research. 2014 Jan 1;53(2):269-78.

Ritchie, Hannah. 2021. How much of the world’s food production is dependent on pollinators? Our World in Data. Retrieved from: https://ourworldindata.org/pollinator-dependence (18-05-2022).

Roy M Francis, Per Kryger, Marina Meixner, Maria Bouga, Evgeniya Ivanova, Sreten Andonov, Stefan Berg, Malgorzata Bienkowska, Ralph Büchler, Leonidas Charistos, Cecilia Costa, Winfried Dyrba, Fani Hatjina, Beata Panasiuk, Hermann Pechhacker, Nikola Kezić, Seppo Korpela, Yves Le Conte, Aleksandar Uzunov & Jerzy Wilde (2014) The genetic origin of honey bee colonies used in the COLOSS Genotype-Environment Interactions Experiment: a comparison of methods, Journal of Apicultural Research, 53:2, 188-204, DOI: 10.3896/IBRA.1.53.2.02

Soland-Reckeweg G, Heckel G, Neumann P, Fluri P, Excoffier L. Gene flow in admixed populations and implications for the conservation of the Western honeybee, Apis mellifera. Journal of Insect Conservation. 2009 Jun;13(3):317-28.

Strange JP, Garnery L, Sheppard WS. Morphological and molecular characterization of the Landes honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) ecotype for genetic conservation. Journal of Insect Conservation. 2008 Oct;12(5):527-37.

Sæther, Liv. 1993. Husdyr i Norden – vår arv – vårt ansvar. Jord og gjerning 1992/1993. p. 97-101. Landbruksforlaget, Oslo.

Read more about our other native breeds

-

Nordland/Lyngen Horse

The first known and documented exhibition where this breed participated, was in 1898 at Lyngseidet in Troms. In the 1930s, organized breeding of Nordland/Lyngen horses started.

Read more about the breed

-

Finnish Landrace Chicken

In 1974, the agricultural advisory agency collaborated with Seiskari and published a call to find remains of the Finnish landrace chicken. As a result, one flock was found in South-East Finland. This family line was named after its geographical location as “Savitaipaleenkanta”.

Read more about the breed

-

Dola Cattle

The Dola cattle originates from Gudbrandsdalen, Østerdalen and Hedmarken, areas north of Oslo. In these areas there were large areas for nutrient-rich grazing, but it was too far to larger cities for the sale of dairy products.

Read more about the breed